sept 2, 2024

cfg and recursive descent parser theory in zig

before we begin, i want to mention what you'll learn by reading this. you'll learn:

- what recursive descent parsing is

- what a regular language and context-free grammar are

- how they are different

- how they relate to lexing and parsing

- how to use our own context-free grammar by building a mathematical recursive descent parser in zig

we wrote a lexer earlier (here), which converted our source code into a list of tokens. this step gave us primitives specific to our language which we can ingest to understand what our program actually means. the next step is to design and implement our language's parser, but that will be done in the next post. this post is about motivating what parsers fundamentally are and how they work.

the importance of determinism

for any given programming language, a list of tokens should only have one "meaning", which defines the actions of the program that will be performed. there should not be ambiguity in what program is generated from the generated list of tokens. it wouldn't be very useful to program in a language that makes no promise on what exactly will be run.

we can abstract this problem to math as well. given an equation of 2*2+4, if we disregard the precedence rules (PEMDAS), then there are actually two outputs we could get: 8 and 12. this is the exact reason math has precedence rules - so that we can map a string of math symbols and numbers into a single deterministic output.

programming languages as mapping functions

we can think of a programming language as a mapping function that takes in a file you can read, and outputs a file your computer can read. just like in math, different inputs can yield the same output, so is in programming languages - there are multiple different source code files you can write with a given programming language that all result in the same output.

this leads us to an important property we aim to satisfy when making our programming language which is a many-to-one relationship between our source code and output executable. catastrophe happens when this relationship is one-to-many (signifies ambiguity in our language).

context-free grammars (CFG)

just like in math, we need a way to derive the value / meaning of a sequence of tokens through "precedence". this introduces us to something called a context-free grammar (CFG).

regular languages vs context-free languages

the language we generate from lexical analysis is most often regular. parsing, on the other hand, most often deals with context-free languages.

-

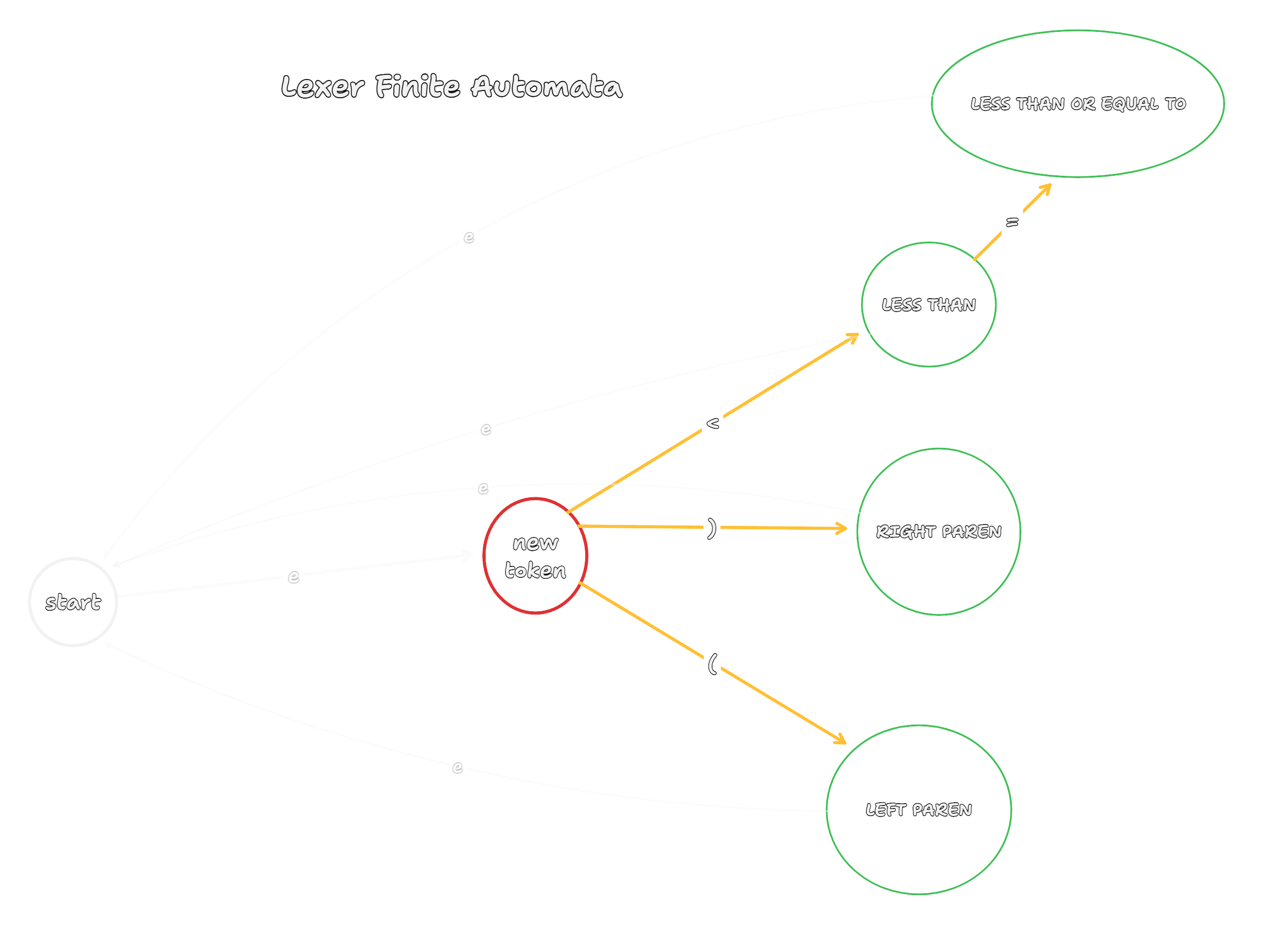

regular language: can be defined with a finite automaton, which is just a fancy type of theoretical machine that has a set of states and a transition function between those states. it can be recognized without using any additional memory beyond the current state.

-

context-free language: requires some memory of where we are coming from, so we can use a stack for that. this is what a pushdown automata (PDA) is.

the image above demonstrates a finite automata that creates a list of new tokens. the language in this case only can read "(", ")", "<" and "<=", so it is a rather limited language but you get the idea.

formalizing our language with cfg

to formalize our language, we can use a context-free grammar which is just a list of rules and characters in our function's alphabet. rules can refer to alphabet characters (known as terminal symbols) or other rules (known as non-terminal symbols), or a combination of the two. let's demonstrate what a grammar for a parser that can read simple math would look like:

MATH → TERM

TERM → TERM '+' FACTOR

| TERM '-' FACTOR

| FACTOR

FACTOR → FACTOR '*' EXPONENTIAL

| FACTOR '/' EXPONENTIAL

| EXPONENTIAL

EXPONENTIAL → PRIMARY '^' EXPONENTIAL

| PRIMARY

PRIMARY → NUMBER

| NUMBER '.' NUMBER

| '(' MATH ')'

NUMBER -> DIGIT NUMBER

| DIGIT

DIGIT -> '0' | '1' | '2' | '3' | '4' | '5' | '6' | '7' | '8' | '9'

here, the alphabet is 0-9, +, -, /, , (, ), .,* and ^. the language is all mathematical expressions which this grammar can generate. an example string this grammar can generate is "(((100 ((((20+4)(22*9+3-3)))))/100)^2)^2". the answer to this mathematical equation is 557256278016 (which you'd know if you stick around for the zig implementation).

disambiguating terms

to disambiguate the term "language", and "alphabet" used for lexers and for parsers let's explain what each refers to:

- alphabet: a function's inputs that it can understand

- language: the set of all possible outputs that function can produce

so in a lexer's case:

- its alphabet is all characters it can read (e.g 'A-z', 0-9, etc.)

- its language would be all tokens it can produce

for a parser's case:

- its alphabet is the set of all tokens it can read

- its language is the set of all possible syntax trees it can generate

there is overlap because one's output is the other's input.

top-down recursive descent parser

the math CFG above demonstrates the set of rules for a top-down recursive descent parser, which we will soon implement. notice the grammar starts with the lowest precedence rules and ends with the highest. this is because a lower precedence expression could be composed of many higher precedence subexpressions which we will need to evaluate before bubbling up to the lower precedence expression for evaluation.

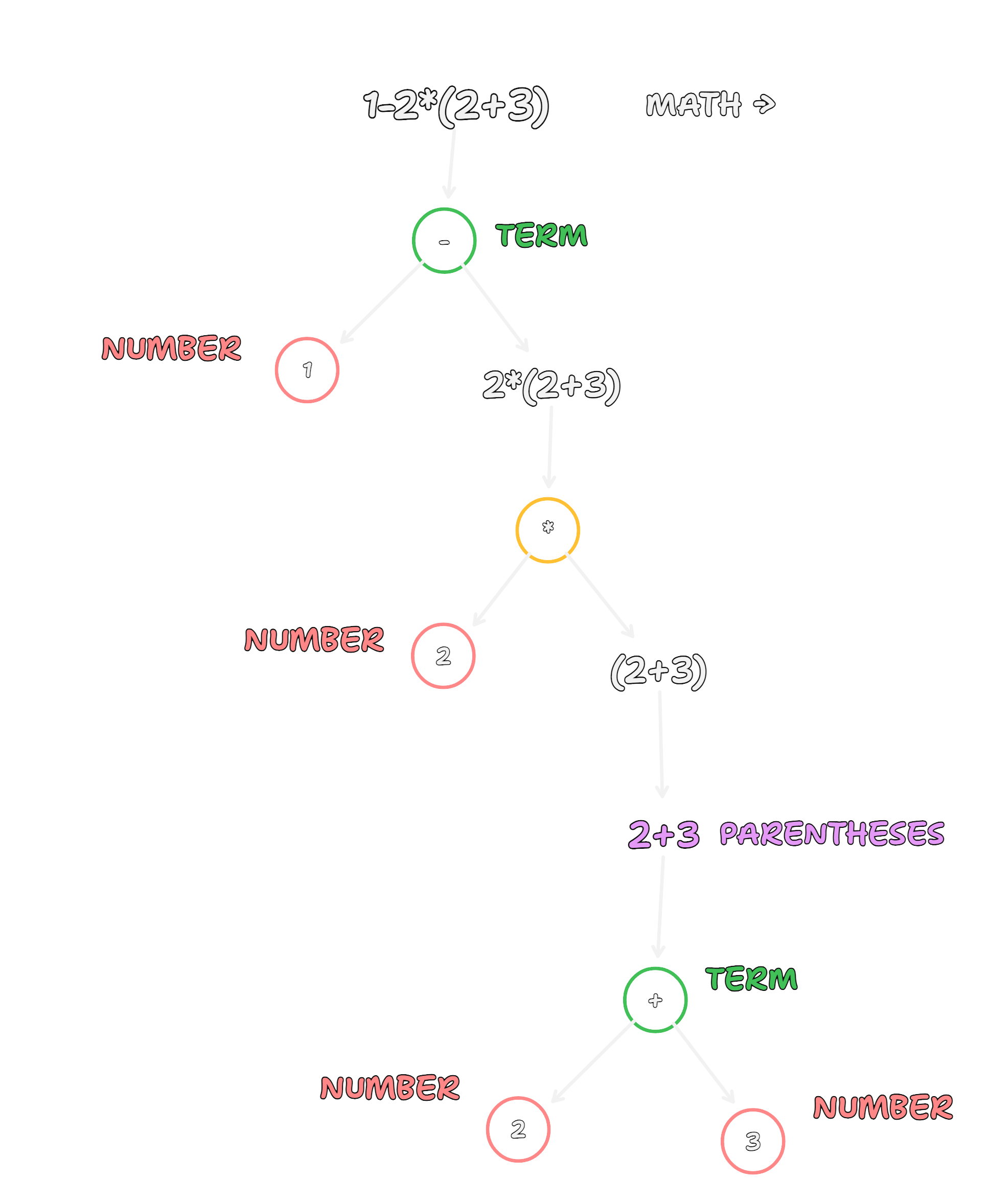

let's take an example expression: "1-2*(2+3)" and draw the syntax tree which this grammar will produce.

we can only execute on binary or unary operations at once, and a math equation we can evaluate is just a set of binary and unary operations. so in order to bubble up to the top, we need to drill down to the bottom, evaluating the expressions at the leaves, then going up a level, and up another level up until we reach the root and can return the final output, which in this case will be -9.

implementing a math parser in zig

now that we have a good enough understanding of CFGs, regular languages and top-down recursive descent parsers, we can implement. we will be building a math parser in zig.

to start, we need to call a function which represents our initial rule in our CFG. in our case, this is the MATH rule. this function will call the TERM function, which will call the FACTOR function, and so on. each function will return a value which will be used in the parent function to evaluate the expression.

the first rule we will build in parserExpr function, and in our grammar the rule just refers to TERM, so this is easy enough to implement.

const std = @import("std");

const print = std.debug.print;

var idx: usize = 0;

pub fn parseExpr(expr: []const u8) usize {

return parseTerm(expr);

}

pub fn main() void {

const expr: []const u8 = "(((10*(100)*((((20+4)*(2*2*9+3-3)))))/100)^2)^2";

const expr_val = parseExpr(expr);

print("{d}\n", .{expr_val});

}

idx is a global variable that will be used to keep track of where we are in the expression. you will see n1 and n2 in each binary operation function, n1 signifies the left side of the operation and n2 the right.

pub fn parseTerm(expr: []const u8) usize {

var n1 = parseFactor(expr);

while (idx < expr.len and (expr[idx] == '+' or expr[idx] == '-')) {

const op = expr[idx];

idx += 1;

const n2 = parseFactor(expr);

n1 = if (op == '+') n1 + n2 else n1 - n2;

}

return n1;

}

now comes all the rest of the functions starting from lowest precedence and going to highest. the lowest precedence function is parseTerm. all functions will take a similar form until parsePrimary which is as follows: we resolve the lhs of the operation which is the return of calling the next higher precedence operation. some higher precedence expression will then increment the global idx, and we will then see if the next character is a '+' or '-' and if so, this operation is in the domain of the parseTerm, which will then go into this while loop and resolve the rhs of the plus or minus operation and compute its value and return it.

parseFactor and parseExponential follow the exact same format so i won't waste time explaning those

pub fn parseExponential(expr: []const u8) usize {

var n1 = parsePrimary(expr);

if (idx < expr.len and expr[idx] == '^') {

idx += 1;

const n2 = parsePrimary(expr);

n1 = std.math.pow(usize, n1, n2);

}

return n1;

}

pub fn parsePrimary(expr: []const u8) usize {

if (expr[idx] >= '0' and expr[idx] <= '9') {

var end = idx;

while (end < expr.len and expr[end] >= '0' and expr[end] <= '9') {

end += 1;

}

const n1 = std.fmt.parseInt(usize, expr[idx..end], 10) catch unreachable;

idx = end;

return n1;

} else if (expr[idx] == '(') {

idx += 1;

const n1 = parseExpr(expr);

if (expr[idx] == ')') {

idx += 1;

return n1;

}

}

return 0;

}

the last function, which has the highest precedence is the parsePrimary function which represents the PRIMARY rule in our CFG. it can either observe a number or a '(', if we see something else to start we need to throw an error because this means there is something invalid in the expression passed into parseExpr.

pub fn parsePrimary(expr: []const u8) usize {

if (expr[idx] >= '0' and expr[idx] <= '9') {

var end = idx;

while (end < expr.len and expr[end] >= '0' and expr[end] <= '9') {

end += 1;

}

const n1 = std.fmt.parseInt(usize, expr[idx..end], 10) catch unreachable;

idx = end;

return n1;

} else if (expr[idx] == '(') {

idx += 1;

const n1 = parseExpr(expr);

if (expr[idx] == ')') {

idx += 1;

return n1;

}

}

return 0;

}

if we see a number as the first character, it can be followed by any amount of numbers, and if we see a dot it should be proceeded by any amount of numbers. on the other hand, if we see a '(', this means there is a grouping going on, so in this case, we should increment the idx by 1 and go to the top rule again to evaluate what is inside these parentheses. we should throw an error if we don't see a ')' after the expression returns but we will just assume the input will be valid for simplicity.

and that's it! i hope you enjoyed. if you did let me know @ x.com/noahgsolomon! we are still so undoubtedly back fam :)